The new Paris Immigration Museum, the Cité Nationale de l’Histoire de l’Immigration, proved so controversial that no senior politician could be found to open it.

Perhaps that’s because, for all of its messages of tolerance and acceptance of difference, it presents what are likely to be, for many, unpalatable truths. The visitor climbs the stairs of the uncomfortably fascist-feeling building (it was built for the International Colonial Exposition of 1931 and the huge facade frieze shows colonial labourers toiling for the empire’s glory) to start their tour beneath a series of maps.

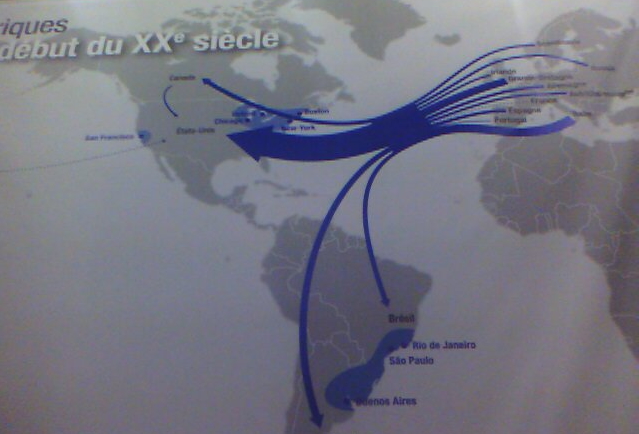

These are facts, presented raw and enlighteningly, movement of people over the past century or so presented as broad sweeping arrows whose width corresponds to the numbers of people on the move.

There’s a powerful reminder that for at least the first half of the 20th century, and certainly at its start, the flows were almost all outward from Europe. It was a continent, it seemed, with huddled masses without hope at home.

And today, when there’s so much concern and discussion about immigration from the Third World to the First, again the arrows tell another story; it is the Third World that is taking the bulk of the strain of desperate human searches for security and safety.

There’s a big flow out of Eritrea into Sudan, but equally large flows from Sudan to Chad and Uganda. Chad is also getting a flow of 100,000 from the Central African Republic, but Chad also saw 20,000 refugees flee into Sudan.

At the end of 20th century the biggest by follow by far is of Mexicans into US – 10.3 million. But Europe also sent 7.5 million people to the US, a flow pretty well matched by thickness of the arrow from India to the Gulf States. These are movements that don’t always get the attention that their size might deserve.

But the main focus here of course, once you get past the maps, is France. Unlike other European countries, it has been mainly a country affected by immigration, not emigration, over the past two centuries. Immigration to France’s still wide open, empty spaces, was unrestricted up until WWI.

Even after that, many of Europe’s displaced from east, south and north arrived, at least on their way to somewhere else. Refugees from the Spanish Civil War are photographed on the French border, peering out of train windows, bored but worried. Wrapped in surely aid-supplied blankets they trudge along a crowded road. There is a disarmed republican brigade in a temporary camp, men between worlds. These might be photos from any of today’s “failed states” or political crises. The kinship is unmistakable.

And no state, it seems, is ever really able to cater adequately for the flood of political disaster. Refugees are everywhere in precarious living conditions, from the Armenians at Camp Oddo at Marseilles, built for 1,200 and finally holding 30,000 in 1923, to Sangatte (which the British tabloids so loved to hate between its opening in 1999 to closure in 2002), that was a temporary, unlovely home to 60,000 over that period.

For some, movement becomes an almost permanent state. The exhibition cites Chileans who as young children were taken by their parents into France as exiles. Then returned to Chile when democracy was restored there – there numbers so great that they got a whole name of their own, retornados.

The focus is very much on individual experience – maps, papers, stuffed toys, the small pieces left of lives torn apart. There’s also a predictable focus on “look what refugees have done” – citing a slightly scatter shot range in, for example, “culture” – Frederic Chopin, Gertrude Stein, Sonia Delaunay, Man Ray, Walter Benjamin, Eugene Ionesco.

Now showing, (until January 7) is a special exhibition of photos from America’s Ellis Island reception centre between 1905 and 1920, when it was the Europeans seeking refuge, although some starting out from better positions than others. Two tatooed German stowaways, “deported May 1911,” look like the types you would think about deporting – hard men who’ve had hard lives.

By contrast there’s Dingenis Glerum from The Netherlands with wife and 11 children in 1907. Cited by The New York Times as the “right sort” of immigrants, the journalist is “pleased to say he was shown wallet with several hundred pounds in it”.

Not much has changed then; I think of Australia’s current immigration law, which allows, almost forces, many to buy their way in – if they can.

The easiest way to reach the museum is by Metro – Porte Dorée (line 8). The captions and audio guide are in French, but even if your grasp of the language is small to non-existent, little here really needs words. The displays are awkward, sometimes overly keen on demonstrating their sensitivity, but there’s still a lot to learn here.